Volumographic reduction is not phenomenological reduction: Theory and drawings on the conditions for describing a human being

Albert Piette

Catherine Beaugrand

2025

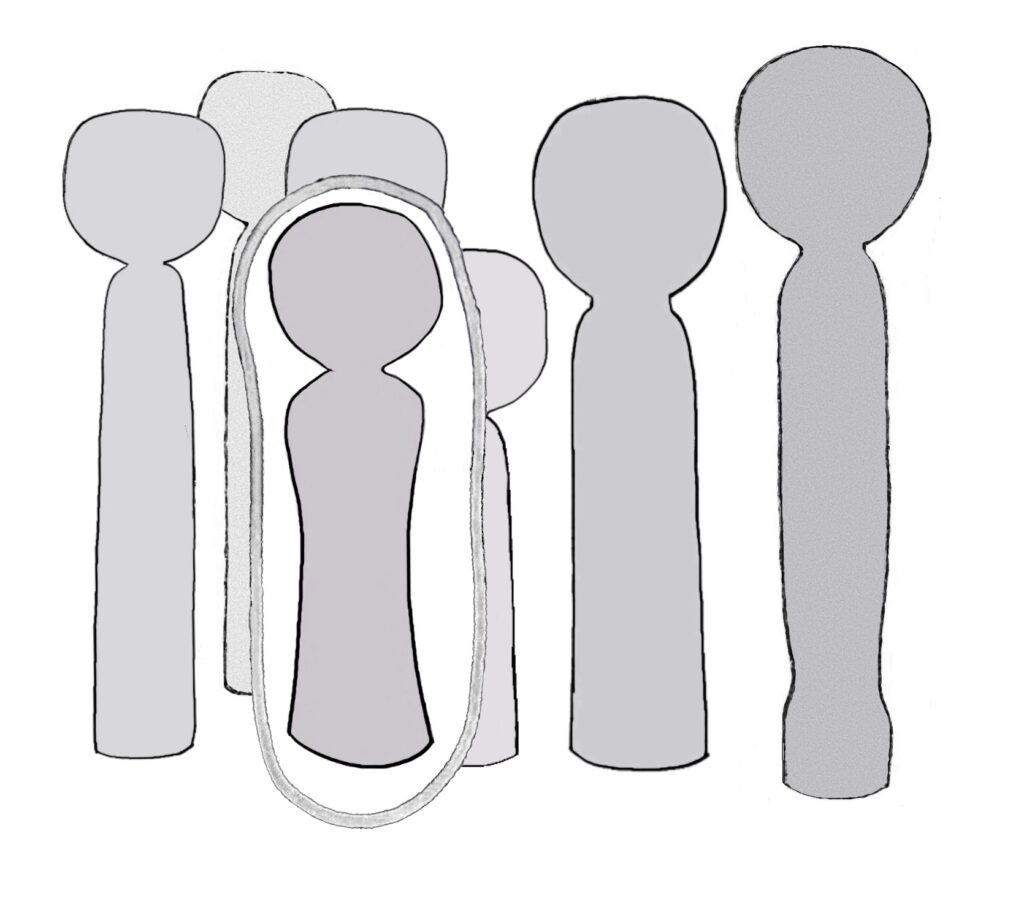

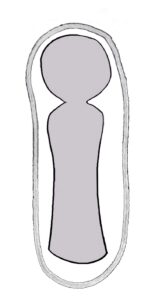

This article reflects on the characteristics of phenomenological reduction in its Husserlian foundation, in comparison with the volumographic reduction advocated by the authors, with the aim of describing and analysing human beings, each in their uniqueness. The authors attempt to show that volumographic reduction has characteristics that are opposed to phenomenological reduction and its use in phenomenological anthropology: it saves each singular entity, does not privilege acts of consciousness, does not value contexts, and does not add other beings. In this configuration of ideas, the authors conclude that there is a kind of affinity between the history of anthropology, which emphasises relations and contexts, and what phenomenological discourse allows in a certain way. The article combines text and drawings that the authors refer to as & quot; drawings of theory & quot; they clarify, motivate, and develop the proposed reading.

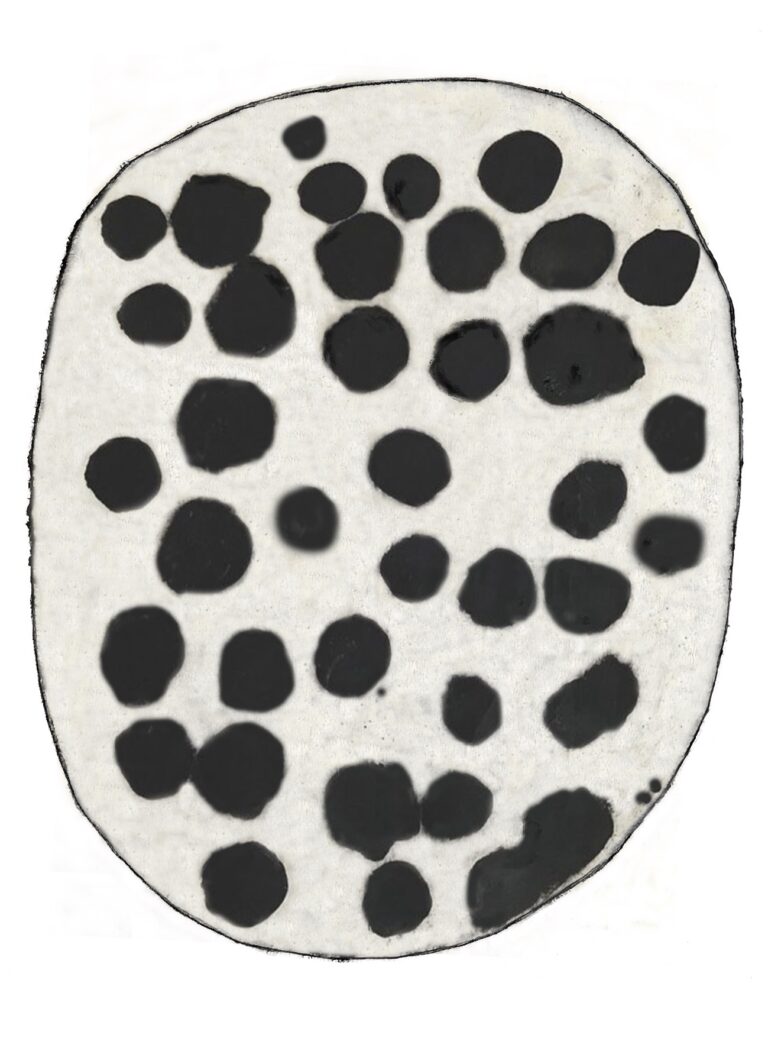

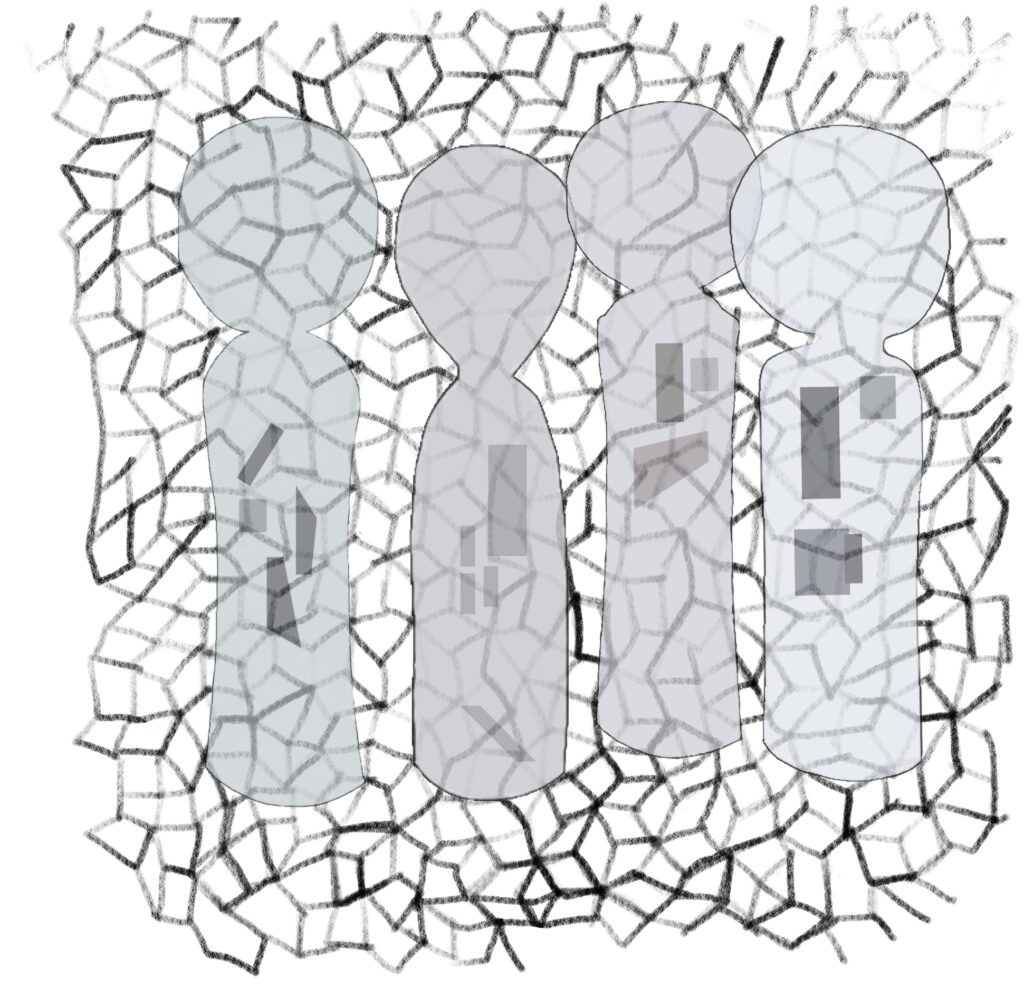

Fig. 1d: There is no volume of being without components that we call “voluments” (elements of a volume of being). They are represented by patches of different sizes to reflect their multiple variations according to the content involved. These voluments are the ones that most often interest the human and social sciences separately: actions, gestures, emotions, language, moods, social or cultural markers, thoughts, memories, cognitive, socio-cognitive or psychological expressions, or even specific stylistic traits, such as mimics or character tendencies.

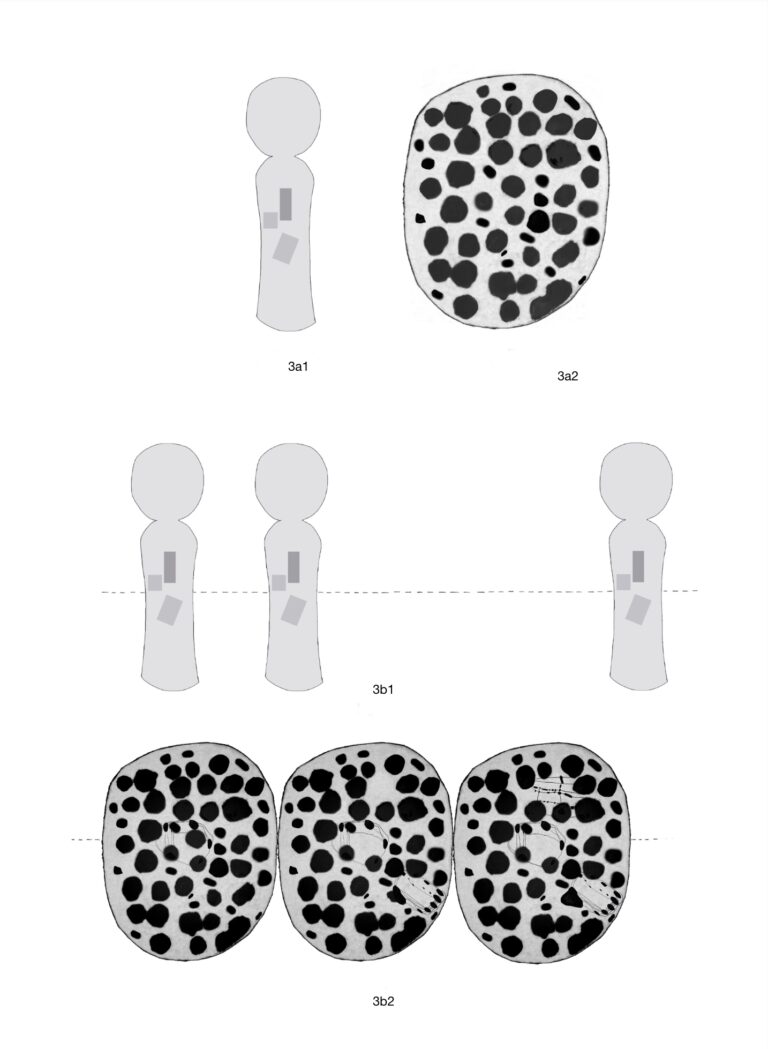

Fig. 3a: Selective focalisation. This consists of choosing a few privileged voluments, represented by small geometric figures in the entity (fig. 3a1) and not the entire volume of being with as many of their voluments as possible (fig. 3a2).

Fig. 3b: Selective focalisation bis. This consists of looking at a few voluments in specific situations and separed moments (fig. 3b1) and not the whole in the strict continuity of moments, revealing different combinations of voluments (fig. 3b2).

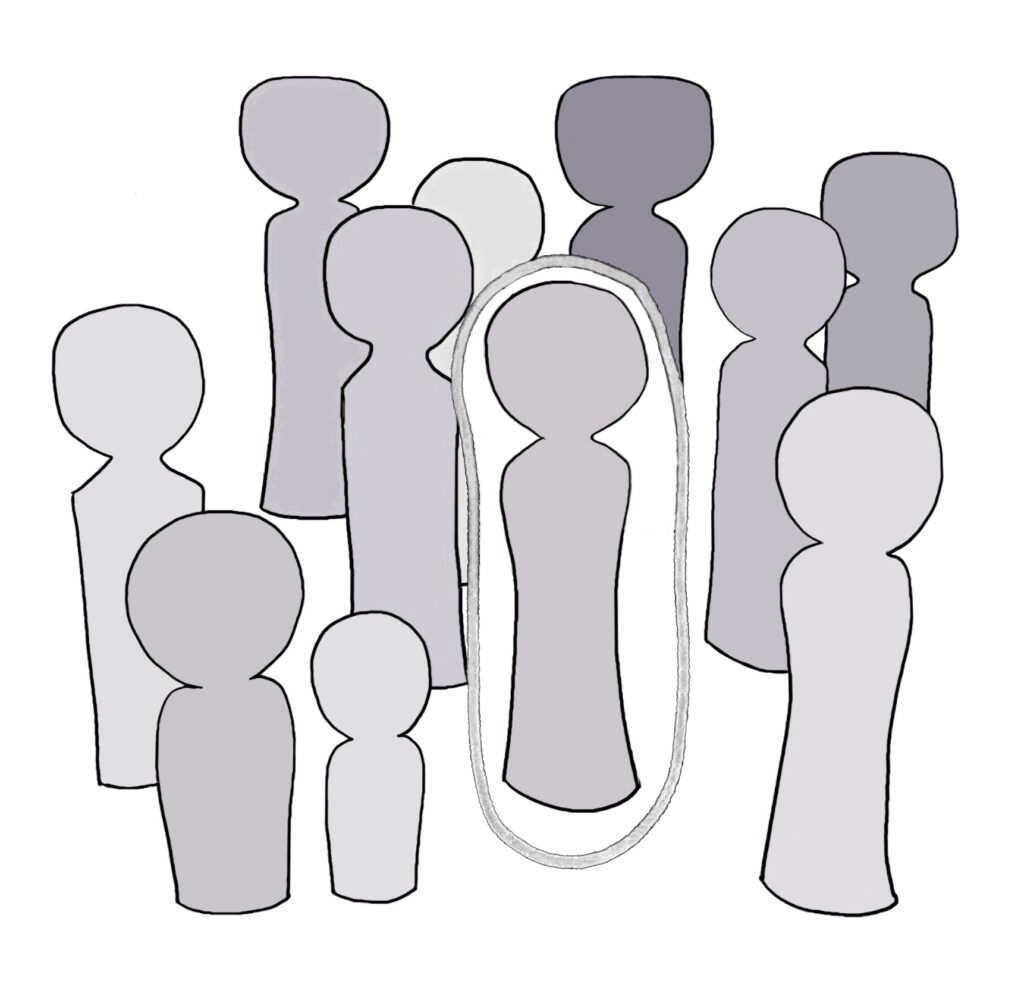

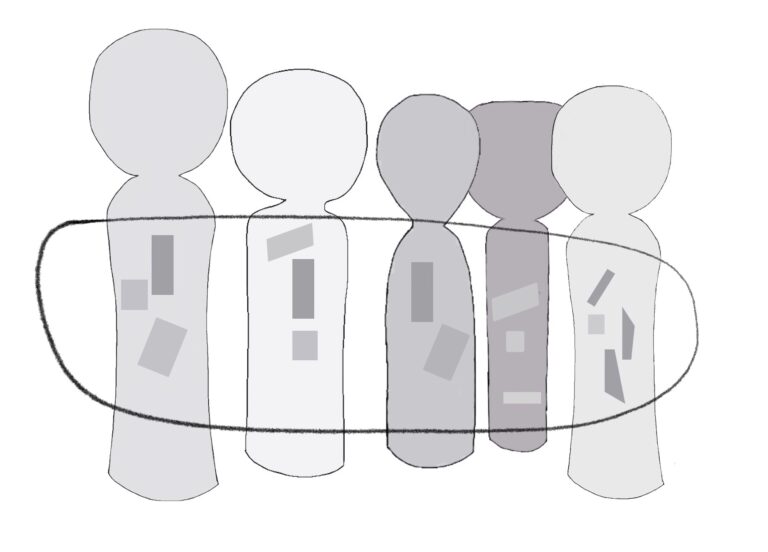

Fig. 3c: Putting together. This consists of homogenising individuals on the basis of voluments that are identical to them (rather than looking at a single being).

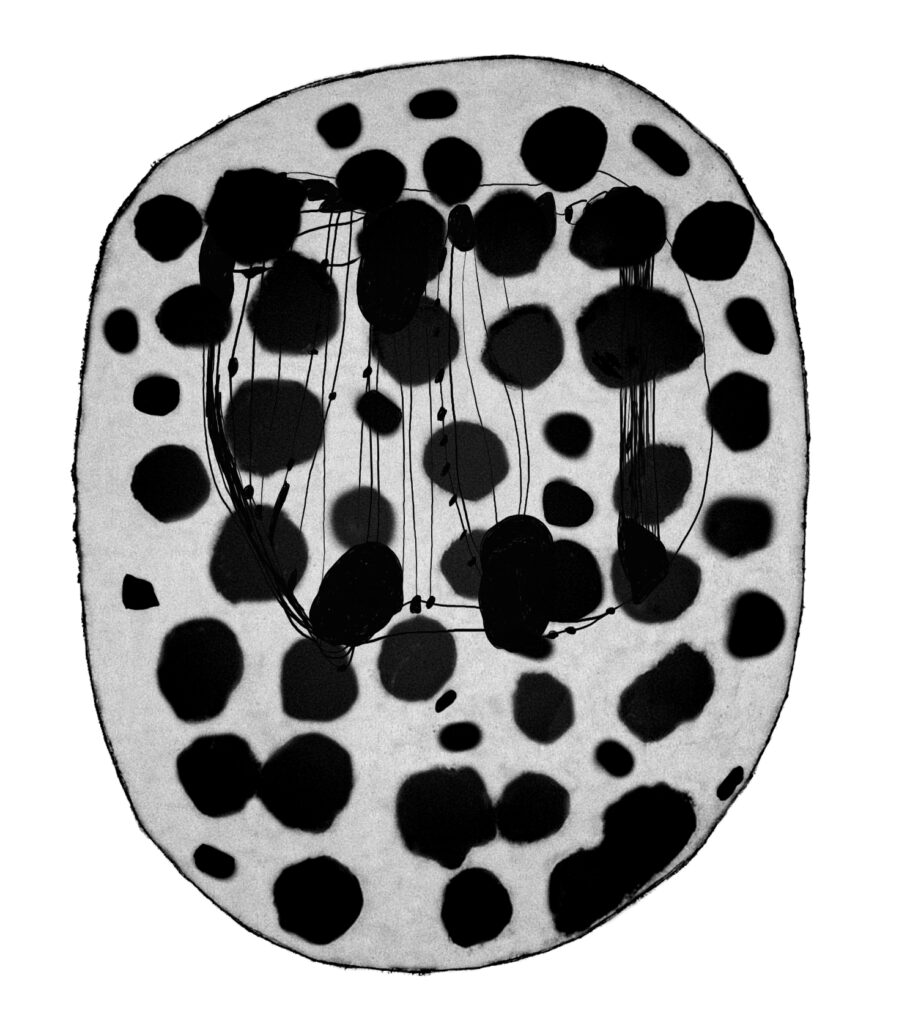

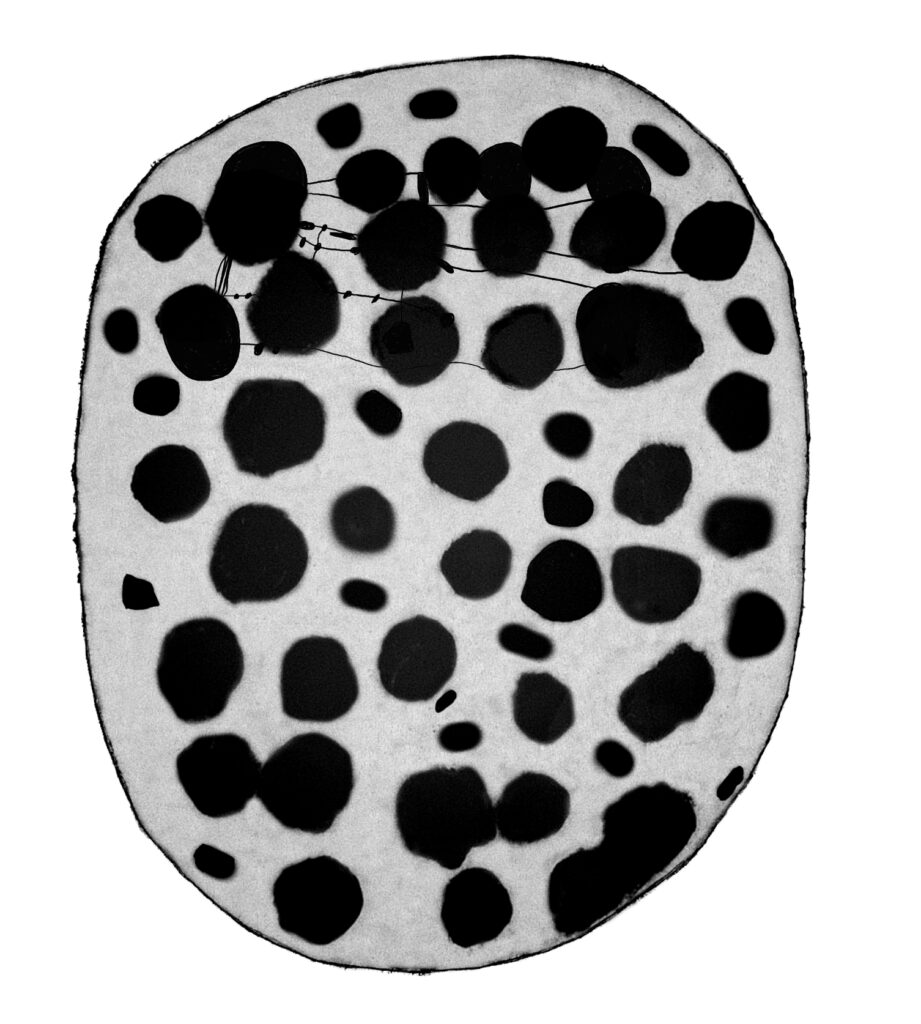

Fig. 3d: Contextualisation. Beings are thought of in a context represented by a background (designating an era, a place, a culture, etc.) into which they are blended. Context is taking on greater importance than humans (fig. 3d1), while volumographic reduction has isolated a volume from their surroundings, without excluding the possibility of identifying contextual traces in the other voluments (fig. 3d2).

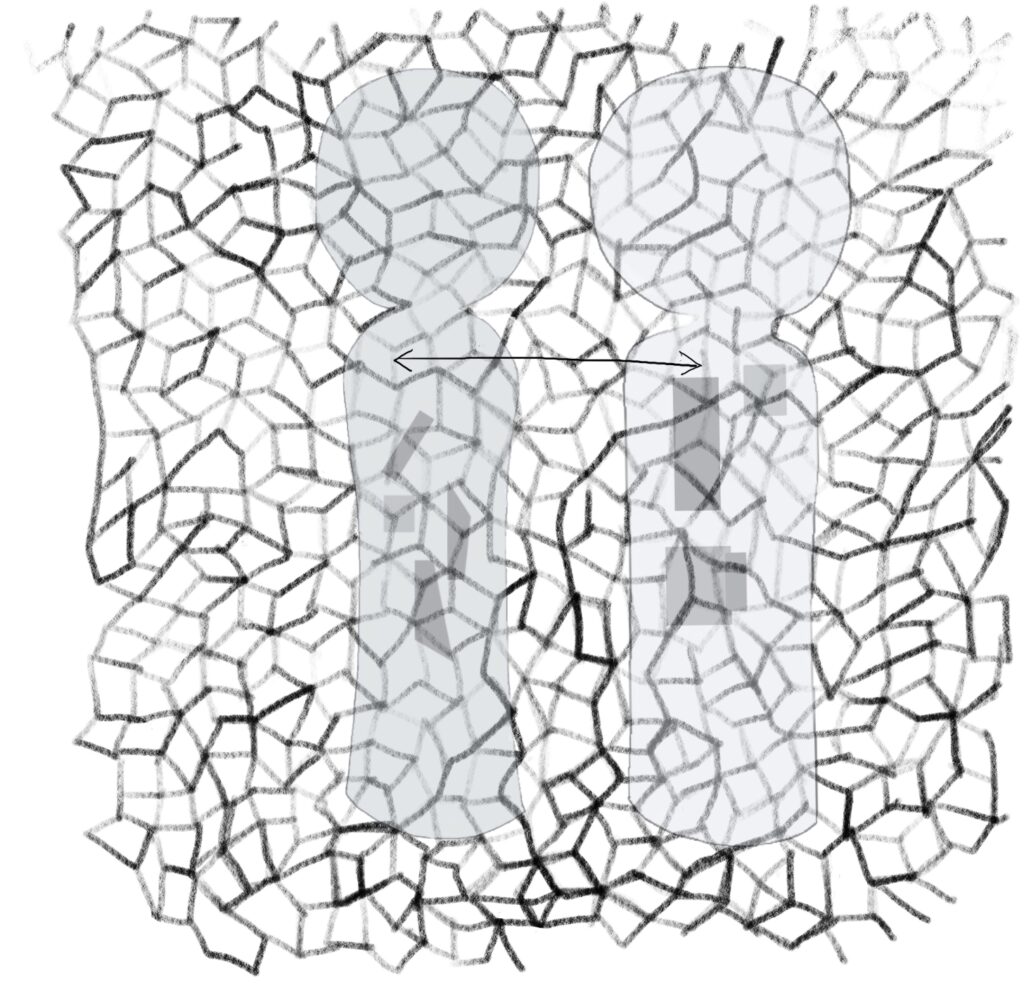

Fig. 3e: Dilution. Placed in a context and in a relationship of intersubjectivity translated by the two- way arrow, the individuals are increasingly diluted (fig. 3e1), while volumographic reduction invites us to study the intracombinations of the voluments, those concerning intersubjectivity and the others (fig. 3e2).